Annotating a Japanese text with word meanings

In my previous post, I segmentized words from a Japanese text, then I searched their meaning via Jisho’s API.

I’d like to improve upon that, and develop a way to annotate the original text with the translations.

While the long-term goal is to have something better presented, my goal for this post will be to generate, given the raw sentence 今日はいい天気ですね。, the annotated sentence: 今日{today}はいい天気{weather}ですね。 .

Goal breakdown

To keep things simple, I’ll focus on kanji-only words, and I’ll only write the first English meaning in braces. So the task is:

Given a text in Japanese, insert a pair of curly braces after each kanji-only word, that contains one English equivalent to that word.

Segmenting text and extracting kanji-only words

I’m reusing the code I wrote previously, but I’m simplifying it a lot.

In fact, last time I used the asyncio module to manage requests to Jisho’s API, which made the whole code unnecessarily complex.

This time, I’m gonna be straightforward as possible.

So here’s a minimal script that takes a file in input, and prints the kanji-only words:

import sys

import regex as re

import nagisa

KANJI_REGEX = re.compile("\p{Han}+$")

def main(path):

with open(path, 'r') as fd:

content = fd.read()

# nagisa.wakati returns a list of segmentized words

segmentized = nagisa.wakati(content)

# I want to isolate kanji-only words, so I just have to filter

words = {w for w in filter(KANJI_REGEX.match, segmentized)}

print(words)

if __name__ == '__main__':

path, *_ = sys.argv[1:]

main(path)

Using the same short.txt as in my last post:

$ python3 segmentize.py short.txt

[dynet] random seed: 1234

[dynet] allocating memory: 32MB

[dynet] memory allocation done.

{'今日', '天気'}

Fetching meanings from Jisho

Since I’m not considering here any performance issue, this part is super easy.

I’ll just import requests and call Jisho’s API:

import requests

API_URL = "https://jisho.org/api/v1/search/words?keyword={}"

def get_meaning(word):

data = requests.get(API_URL.format(word)).json()['data'][0]

return data['senses'][0]['english_definitions'][0]

def main(path):

with open(path, 'r') as fd:

content = fd.read()

words = segmentize(content)

meanings = {word: get_meaning(word) for word in words}

print(meanings)

Here’s the new output of the script:

$ python3 segmentize.py short.txt

[dynet] random seed: 1234

[dynet] allocating memory: 32MB

[dynet] memory allocation done.

{'天気': 'weather', '今日': 'today'}

Alright, let’s move on to the text annotation.

Annotating the input text with meanings

For this step, I’ll use the output of nagisa.wakati, that is the input text segmented, and recreate the original input from that, with added annotations.

I will form the output using io.StringIO, which is similar to Java’s StringBuilder in that it’s a performant way to iteratively append characters to a string and only then get the string’s value.

Again, the code is pretty simple:

def main(path):

with open(path, 'r') as fd:

content = fd.read()

segmentized = nagisa.wakati(content)

words = {w for w in filter(KANJI_REGEX.match, segmentized)}

meanings = {word: get_meaning(word) for word in words}

output = io.StringIO()

for word in segmentized:

# StringIO.write appends a string at the end of the buffer

output.write(word)

if word in words:

# Since I chose to write the annotation inside curly braces,

# I cannot use the common formatting, but I can use % instead

output.write("{%s}" % meanings[word])

print(output.getvalue())

The output is exactly what we expected:

$ python3 segmentize.py short.txt

[dynet] random seed: 1234

[dynet] allocating memory: 32MB

[dynet] memory allocation done.

今日{today}はいい天気{weather}ですね。

So far, the script is as short as 36 lines:

import io

import sys

import regex as re

import nagisa

import requests

API_URL = "https://jisho.org/api/v1/search/words?keyword={}"

KANJI_REGEX = re.compile("\p{Han}+$")

def get_meaning(word):

data = requests.get(API_URL.format(word)).json()['data'][0]

return data['senses'][0]['english_definitions'][0]

def main(path):

with open(path, 'r') as fd:

content = fd.read()

segmentized = nagisa.wakati(content)

words = {w for w in filter(KANJI_REGEX.match, segmentized)}

meanings = {word: get_meaning(word) for word in words}

output = io.StringIO()

for word in segmentized:

output.write(word)

if word in words:

output.write("{%s}" % meanings[word])

print(output.getvalue())

if __name__ == '__main__':

path, *_ = sys.argv[1:]

main(path)

Bonus: Making a simple visualization tool

Alright, we have annotated the input text. However, this is definitely not readable. What’s more, the annotation is very poor, but if we were to add information such as pronounciation and more meanings, this would become an absolute mess. So here’s what I’m gonna do: a very simple visualization tool, using HTML and CSS. To be more precise, I’m gonna use HTML to annotate the output text, rather than those impractical curly braces. There are tons of possible ways to do this, but I’m gonna stay simple and implement the approach described in this StackOverflow post.

The annotated text is a slight bit more complex than before, but not much: I just enclose the word in a <span> tag, with a meaning attribute.

for word in segmentized:

if word in words:

output.write(

"<span meaning='{meaning}'>{word}</span>".format(

meaning=meanings[word],

word=word

))

else:

output.write(word)

Then, instead of simply printing the output, I write it to an output.html file.

In a real-life application, I would use Jinja and a clean template for this purpose, but for now I’ll naively write the HTML code in the Python script:

with open("output.html", 'w') as fd:

fd.write(

"""

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="style.css" />

<meta charset="utf-8"/>

</head>

<body>

{}

</body>

</html>

""".format(output.getvalue())

)

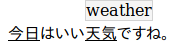

With very basic styling, this is the output I created:

Conclusion

Here we are now: from a text written in Japanese, we are able to annotate the words written in kanji, and to present it in a readable and dynamic appearance. I’ll admit that the presentation is rather austere, and that the information it displays for each word is far from complete. But the concept is here; we can easily add more of the information fetched from Jisho to the tooltip, and the visual aspect of the reader can also be improved without to much difficulty.